(Argus, 30.Oct.2020) — The region’s recovery from Covid-19 will depend heavily on who is dictating US policy, writes Patricia Garip.

Waves of political chaos that recurrently engulf Latin America were not supposed to wash up on stable US shores. Yet days before the 3 November election, the US is convulsed by claims of ballot meddling, threats of violence and a leader questioning the electoral process. This scenario is familiar to Caracas, not Washington.

Because Latin America relies heavily on US trade, investment and monetary policy, the turmoil is unsettling. Whether incumbent Donald Trump wins another four years, or loses to Democratic former vice-president Joe Biden — as the polls predict — the result will shape the pace and direction of Latin America’s economic recovery from the disproportionately harsh impact of Covid-19.

The IMF forecasts that Latin American and Caribbean GDP — coming off zero average growth in 2019 — will shrink by 8.1pc in 2020, before rebounding to 3.6pc next year. If Trump prevails, this tentative recovery is more likely to be driven by traditional commodity exports, reinforcing the mandate of national oil companies such as Mexico’s Pemex and Brazil’s Petrobras, while promoting US oil investment in hotspots such as deepwater Guyana and Colombia’s fledgling shale play.

But Trump’s isolationist “America First” strategy could also usher in higher trade barriers, more explicit pressure on Latin America to spurn Chinese investment and financing, and a deeper rejection of the multilateralism that has long underpinned the region’s economic and institutional development. With the election behind him, Trump’s loud but ineffective “maximum pressure” campaign on Venezuela would further unravel, leaving a potential void superficially cloaked by Monroe Doctrine sentiment. More consequentially, his climate denialism would make it easier for Latin America to avoid a greener path to economic growth.

In contrast, a Biden administration would incorporate climate goals into foreign policy, encouraging the region to accelerate its energy transition and step up environmental standards. Similarly, Biden’s labour commitments would raise the trade bar. Strategic minerals exporters such as Chile would be well-positioned to supply the raw materials needed to fulfil Biden’s green manufacturing plan. Others such as Ecuador and Colombia that remain glued to oil for most of their foreign earnings would have incentives to diversify.

Biden’s plan to re-engage with multilateral organisations, return to the Paris climate accord and realign with EU allies would seek to restore US global leadership and send more consistent transatlantic policy signals to Latin America. But his climate focus would also risk antagonising oil-focused neighbours such as Mexico.

Who’s on first?

They got off to a rocky start, but relations between Trump and Mexican president Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador warmed up once a revised US-Mexico-Canada (USMCA) free trade deal was agreed in 2018. The two nationalists have a common disdain for climate policy and an affinity for oil and coal. But energy ties are inexorably lopsided, with Mexico by far the top importer of US oil products and natural gas — a structural dependence that Lopez Obrador’s anachronistic greenfield Dos Bocas refinery project will not erase (see chart). By the same token, US refiners exporting products will continue to rely on Mexico and other Latin American markets whatever the election result, while US demand lags pre-Covid levels.

Despite their energy interdependence, US-Mexico relations in a second Trump term would probably remain shallow, as long as co-operation on immigration — a key issue for Trump voters — stays on track. Trump threw Lopez Obrador an unexpected lifeline in April with a nominal pledge to reduce US oil production so that Mexico could fulfil a commitment to Opec+. Lopez Obrador’s rollback of Mexico’s 2014 energy reform — and the Trump administration’s tepid response to US investors’ recent complaints of Mexican regulatory bias — show that the White House is even willing to tolerate Mexico First.

A Biden administration would press Mexico to fulfil USMCA investment commitments, with added environmental and labour expectations. It would offer incentives for Mexico to reopen the energy sector, but with a greener accent aligned with US climate goals, implicitly recognising that investors will have less appetite for oil assets by the time Mexico elects its next president in 2024.

Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro is another nationalist, but unlike Lopez Obrador he boasts a reform agenda crowned by the downsizing of Petrobras. While Mexico is building a refinery and propping up Pemex, Petrobras is divesting refineries and retrenching into its core pre-salt business, opening US investment opportunities. As in Mexico, the US is Brazil’s leading foreign investor. But China has emerged as an increasingly relevant commercial partner because of its resurgent pre-salt crude demand — a strategic relationship that belies the rhetoric of Bolsonaro and Trump.

Under a Trump or Biden presidency, China’s oil buying spree in Brazil would remain intact. But another Trump term would likely see more tariff flare-ups with Brasilia, as happened with steel and ethanol this year. Biden’s plan to incorporate environmental commitments into trade relationships would pressure Brazil into tackling runaway Amazon deforestation.

Lost cause

One place where Biden’s green agenda would not immediately resonate is Venezuela, where the Trump administration’s years-long quest to topple President Nicolas Maduro in favour of opposition leader Juan Guaido has already started to fade. While Maduro has overcome US sanctions that he blames for Venezuelan hardship, Guaido’s popular support has slumped. His nostalgic oil-based reconstruction plan for Venezuela looks obsolete, and many of his exiled advisers who helped draw it up have abandoned him. Even his mentor, Leopoldo Lopez, has left the country. Many US allies no longer accept Guaido as the exclusive democratic option, and December legislative elections that the mainstream opposition has vowed to boycott could end his leadership for good.

In a desperate two-for-one strategy this year, the White House is playing up threats posed by Maduro’s ties to Iran, with few adherents beyond hardline opponents still believing that Trump is committed to “all options”.

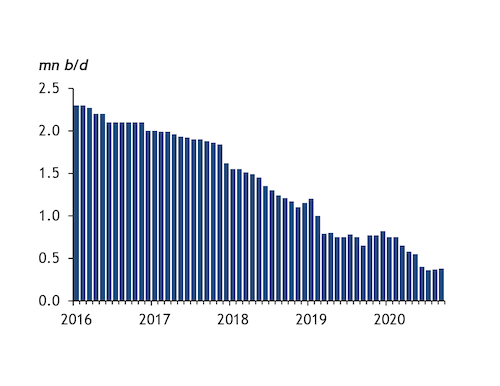

If Biden succeeds Trump, US sanctions on Venezuela would not disappear. And even if they did, Venezuela’s oil industry is too far gone to meaningfully rejoin the market in the way that Iran’s could (see chart). But Biden would broaden the sanctions exit route to give Maduro and his military backers more incentives to hold credible elections. In parallel, Biden would move closer to the EU’s diplomatic approach, and resume a thaw with Cuba that was spearheaded by Trump’s predecessor Barack Obama. Overall, Biden would “de-Venezuelanize” policy toward the region, and offer temporary US protection for Venezuelan immigrants.

Whether Trump wins or not, come November he will no longer need to beat the drum over Venezuela and Cuba to win over conservative Latino voters in Florida. He could let Wall Street bondholders execute their claim to Venezuelan state-owned PdV’s US refining subsidiary Citgo. Disillusioned with Guaido, Trump could even meet Maduro in a dramatic sequel to his North Korea summit.

For now, hopes for a peaceful transition are better applied to the US than to Latin America, where Bolivia and Chile are the latest countries to celebrate orderly elections. But even after the US votes are counted, the surging pandemic will force the man in the White House to look inward before looking south.

Venezuela crude output

__________