(Ft.com, Bryan Harris and Andres Schipani, 24.Apr.2019) — Castello Branco knows Brazil oil group needs to show autonomy to regain investor trust.

Roberto Castello Branco, the new chief of Brazilian oil company Petrobras, was thousands of kilometres away from his desk, at a conference in Chicago, when he faced his first crisis.

It was a Friday afternoon and Jair Bolsonaro, the Brazilian president, had just announced he would cancel a scheduled increase in the price of diesel. The decision was designed to stave off a potential truckers strike, which Mr Bolsonaro feared could paralyse the country.

But it also sent shares in Petrobras into freefall, knocking about $8bn off its market capitalisation. Investors also feared it showed that Brazil was returning to the bad old day of government intervention under a president who freely admits he knows nothing about economics.

“It was a blip. We don’t want to return to this past,” said Mr Castello Branco, rebuffing claims of state intervention in his first interview since the market crash.

Softly spoken and wearing blue jeans, Mr Castello Branco — who took the reins of Brazil’s largest company in January — appears more like a liberal arts professor than the president of an oil and gas giant with a market cap of about $100bn.

Yet he is a key member of a cohort of University of Chicago-educated economists who have come to dominate the top tier of Brazilian business and policymaking since the election of Mr Bolsonaro.

“I went there to Brasília, and showed [the president] the numbers, the explanations. He understood me and said that he doesn’t want to intervene and he can’t intervene,” said Mr Castello Branco, who estimates that the previous government’s efforts to subsidise diesel prices cost Petrobras some $40bn.

Bolstering the independence of Petrobras has become a central objective for Mr Castello Branco. The stark reality is that he has little other choice if he is to rehabilitate the company’s name in investors’ eyes.

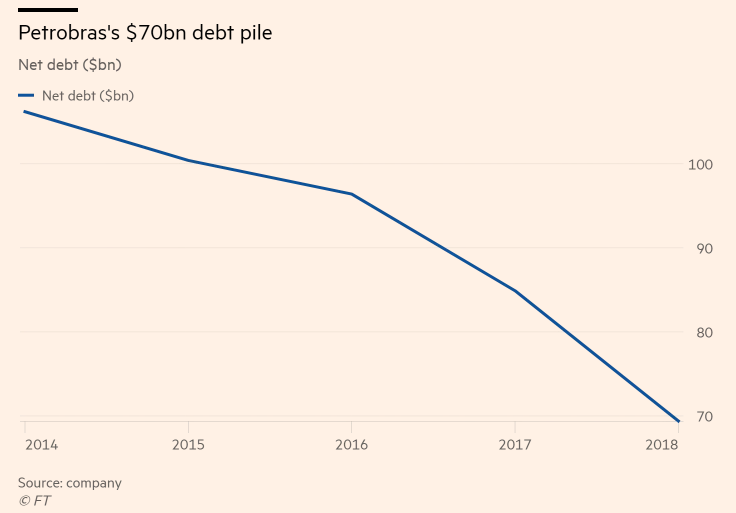

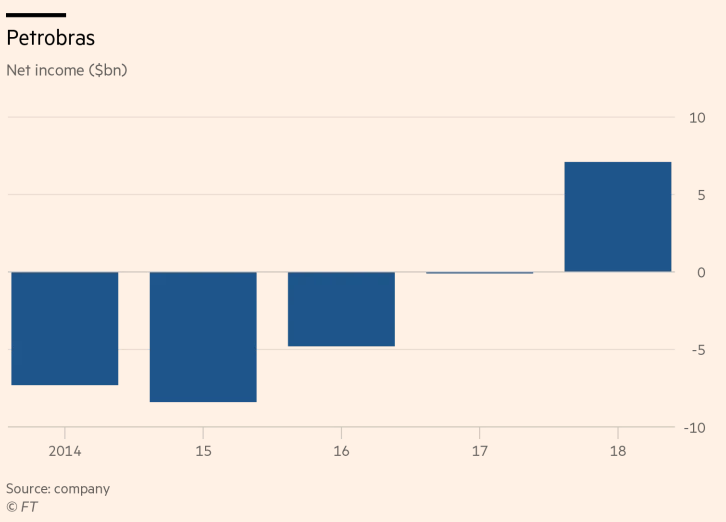

Among the previous government’s legacies for Petrobras are Brazil’s largest-ever corruption scandal, years of losses and a $70bn debt pile — in part due to subsidies the company was obliged to provide to Brazilian consumers

“Anything that impedes Petrobras’ healthy commercial operation can cause problems. How big can these problems be? We need to see how much these influences will now allow Petrobras to be managed as a more efficient and profitable company,” Alejandro Werner, the head of the International Monetary Fund’s western hemisphere department, told reporters recently.

Luiz Francisco Caetano, an analyst with Planner Corretora, puts its more bluntly: if the government starts interfering, nobody will be interested in buying Petrobras’ assets.

That issue cuts to the heart of Mr Castello Branco’s agenda, which seeks to reduce Petrobras’ debt load via $27bn of asset sales.

The executive says the company has “lots of things” to sell, including gas pipelines, its retail distribution business and refineries.

Earlier this month, the company agreed to sell its TAG gas pipeline in northern Brazil to a consortium led by France’s Engie for $8.6bn — its biggest divestment to date.

“Although there has been a deleveraging process since 2015, we still have a large debt in absolute terms, but also in relation to cash flow generation. We are much more leveraged than is recommended. We can see this very clearly when we compare Petrobras with its global peers,” said Mr Castello Branco.

Perhaps the most contentious planned sale would be Petrobras’ monopoly position in refineries. Mr Castello Branco, brandishing his Chicago boy credentials, said the situation was “not consistent with free society”.

Such monopolies, even among so-called national champions, “reduces freedom of choice and generates distortions in the economy”, he said.

“It is not good for monopolists [either] because the tendency is to become fat cats,” he said.

The company’s efforts to cut debt have been matched by a return to profit last year for the first time since 2013. The company reported net income for 2018 at R$35bn ($8.9bn), while its ratio of net debt to earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortisation fell to 2.34, beating the company’s goal of 2.5.

By comparison, global oil majors have an average net debt/ebitda ratios of 1.44, according to Bloomberg data.

The improved results reflect twin developments. The first is Petrobras’s successful exploration and extraction of “pre-salt” oil, located below a thick salt crust in deepwaters off the coast of Sao Paulo and Rio de Janeiro.

“Ten years ago pre-salts was an idea . . . maps on the wall. Now [Petrobras] is producing 1.5m barrels a day and it will continue to increase,” said Joaquim Levy, president of BNDES, Brazil’s development bank.

André Hachem, an analyst with Itau in Sao Paulo, estimated that production of more than 2.5m barrels per day would grow “very fast at 10 per cent this year and around 10 per cent next year”.

Petrobras’s technical and technological prowess, however, have been famously overshadowed by a reputation for corruption that cut to the heart of the company.

The group was at the centre of the sprawling Lava Jato, or Car Wash, investigation that implicated hundreds of Brazilian politicians and businessmen in a vast contracts-for-kickbacks scheme.

Mr Castello Branco said he had continued the work of his predecessor, Pedro Parente, in bolstering compliance. The company now has about a 400-strong team to weed out malfeasance.

“I believe Lava Jato made a great contribution to the future of this country,” he said. “There is no such thing as a sure thing. But if corruption exists in Petrobras, it is an isolated case.”

Meanwhile, Mr Castello Branco and the government’s business team appear to have been successful in teaching Mr Bolsonaro some economics.

Days after the Friday crash and Mr Castello Branco’s journey to Brasília, Petrobras pushed ahead with a diesel price rise, and its share price has since regained some ground.

Unfortunately for the administration in Brasília, however, the truck drivers are once again considering action.

Additional reporting by Carolina Unzelte

***