(Oilprice.com, Viktor Katona, 12.Nov.2018) — I know what you think – such a headline is quite reckless given that Guyana has not produced any oil so far and it is not until 2020 that we can actually start talking about a Guyanese oil miracle. Still, Guyana is one of the hottest exploration regions globally, in just three years ExxonMobil has managed to realize nine impressive finds, totaling around 4 billion barrels in reserve. And this is just the beginning – further exploration will inevitably elevate Guyana into the ranks of South American leaders. Now where does this leave Senegal and the Gambia? Well, if one is to accept my somewhat precipitated assumption, many similarities are to be discovered between Senegal and Guyana, pointing to the direction of big discoveries coming very soon.

The Senegal Basin and the Guyanese Basin are by-products of the same tectonic developments in what used to be West-Gondwana, where intra-continental rifts developed in Cretaceous sedimentary basins. As a result, both sides of the Atlantic Margin are structurally and compositionally similar. Yet Guyana has always ranked somewhat higher than the Senegal Basin – the vicinity of oil-prolific Venezuela has always jangled the nerves of ambitious oilmen, whilst Senegal was largely overlooked. To illustrate the point – when the USGS conducted an assessment of the Senegal Basin reserves in 2003, the discovered oil reserves at that point stood at a mere 10MM barrels of oil, whilst gas resources amounted to 49BCf. That, of course, has changed after the largest oil and gas find of 2017, which, having been under the radar of leading news outlets, was the Yakaar field in offshore Senegal.

The deepwater Yakaar field was discovered last May, confirming Kosmos Energy’s expectations that it would contain 15 TCf of reserves. Yakaar, together with the development of the Greater Tortue Complex offshore Mauretania with some parts crossing into Senegalese waters, provide a solid foundation for creating two relatively low-cost LNG clusters in the area. The results attained heretofore several important questions – what do relevant countries (Mauretania, Senegal, Gambia, Guinea Bissau and Guinea) expect from their hydrocarbon endowment? Would they prefer gas reserves instead of oil? Any answer would most likely be vacillatory because the Senegal Basin has so far mostly unfolded gas fields, with only partial success in drilling for oil. The truth is that all Senegal Basin nations would love to set their sights on oil (easier to monetize and use), Senegal is a fitting example of how it could use it.

Senegal’s oil product consumption grows by an annualized rate of roughly 4%, making the task of upgrading the energy sector increasingly time-sensitive. For this, it would need not only oil, but also downstream infrastructure, which currently is sparse and unsophisticated. However, the only refinery in the country, the 25 kbpd Mbao refinery built in 1963, will not be able to cater for Senegal’s needs – in a highly dieselized country, it is expected that product demand would more than double in the next 20 years from the current 47kbpd to 115kbpd. It would also place Senegal in a more comfortable position as the government could renounce on buying Bonny Light and Erha from Nigeria, albeit at discounted prices, and could fully rely on its own production.

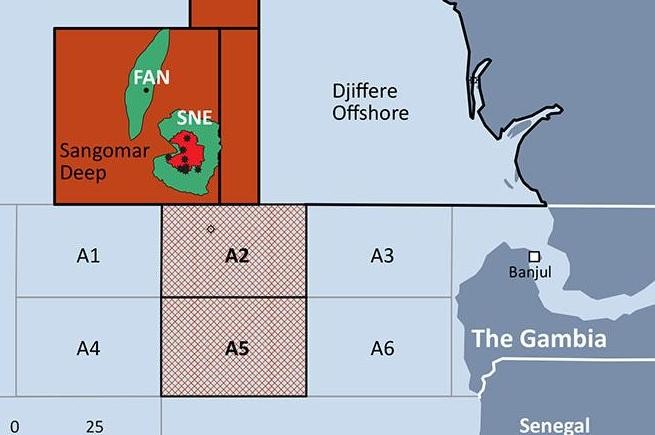

Amid several large gas finds, so far there has been only one noteworthy oil discovery – the first deepwater well in Senegalese waters in 2014 found the SNE field in Albian sandstones at a depth of 1.4km. The SNE field contains, according to the operator Cairn Energy, 3C reserves of 998MMbbl which could allow it to reach a plateau production late 2020s of 140kbpd – the start of the field is expected to take place in 2022-2023. Oil from SNE would be fed into a FPSO with subsea tie-backs. Some 20km to the north of SNE, another discovery, FAN, is showing some potential, too, with estimated reserves ranging from 250-900MMbbl. The hydrocarbon column which the drillers found was more than 500 meters long, with the net oil column being 29 meters.

The Gambia tries to keep abreast with regional developments, having drilled the first offshore well, Samo-1, in late October after almost 40 years of idleness. The Samo-1 well is located in Gambia’s Block 2, to the south of Senegal’s SNE fields – meaning that most likely it shares its geological structure, meaning Maastrichtian sandstones that most likely contain light oil with a 32-33° API density. A positive result (the operator FAR expects that it will find around 825MMbbl of) would extend the oil-bearing play across the Senegalese-Gambian border and hype up the resource potential of the Senegal Basin. Yet as opposed to Senegal, which has fought long-standing battles with its own populace and interest groups on how to deal with its hydrocarbon resources, the Gambia fully lacks the institutional framework to manage its oil and gas.

Source: API.

Now back to the Senegal-Guyana comparison. One of the most interesting trends across the Atlantic is that companies which have serious positions in either Guyana or Senegal are currently trying to establish themselves on the other side of the Atlantic. ExxonMobil, which has by far played the most important part in developing offshore Guyana, clinched 3 deepwater blocks in offshore Mauretania (i.e. the part of the Senegal Basin which is most likely to contain oil) and seeks to use its profound Guyana-relevant knowledge to appraise the stratigraphic traps along the African shore. It works the other way round, too – Total, the most powerful major present in Senegal, built on the intense Franco-Senegalese ties, has entered Guyana this year, acquiring interests in the Canje, Kanuku and Orinduik Blocks.

Thus, do not be surprised if in five years’ time Senegal or Mauretania becomes one of the hottest locations for oil majors – after several decades of torpor, partially thanks to the efforts of some risk-taking independent companies, the Senegal Basin has emerged as a genuinely attractive play with some top-quality fields (e.g.: the SNE field’s breakeven oil price hovers around 40 USD per barrel). The plays are similar to Guyana’s – something which majors familiar with the structure of the Atlantic Margin have already noticed, with Total and ExxonMobil placing their bets on both sides of the ocean. Senegal’s similarities with Guyana, however, do not end with the characteristics of the fields and plays in question. Institutionally, it might still not be ready for the administration of the burgeoning oil sector.

Senegal’s national oil company Petrosen has issued a call for expressions of interest on deepwater offshore blocks to the south of Gambia’s A4 and A5 blocks, which it deems might contain up to 1.5 billion barrels of oil equivalent. It counts on the participation of oil majors – Total is sure to play a very active role in any licensing round that takes place, as well as Petronas (the operator of Gambia’s Samo-1 well). Yet for this, Senegal first ought to clarify how would the new petroleum code look like – will PSAs be a preferred variant or will it apply concessionary agreements, too; will it introduce a petroleum export tax and if so, to what extent would it do harm; how strict would local content requirements be? It is only after all these questions are clarified that international majors will rush to the new hydrocarbon-rich region.

***

#LatAmNRG