(Rystad, 11.Jul.2018) — Despite the huge potential from pre-salt basins, Brazil still needs gas imports to cover domestic demand in the next decade. Brazil is forecasted to produce 47 Bcm of gas in 2030 with low production costs from developments in the Santos and Campos basins. However, as the current offtake capacity from the offshore operations to mainland has already proven to be a bottleneck for marketed gas growth, new infrastructure is critical for future growth. Furthermore, gas demand is extremely volatile and could oscillate between 40 Bcm to 57 Bcm by 2030 due to the high dependence on hydropower, which in turn is highly dependent upon precipitation patterns. So while we see continued pipeline imports from Bolivia and LNG imports, the levels are uncertain. Nevertheless, during normal precipitation years, we forecast that lower Bolivian gas imports will make room for greater growth in LNG imports.

Production

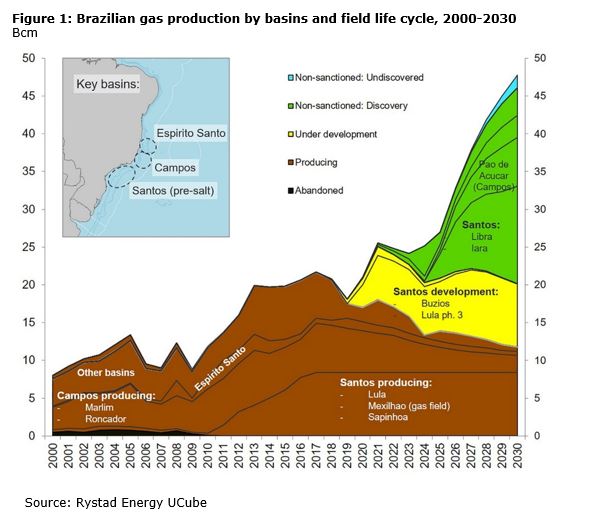

Over the last years, gas production in Brazil has been growing significantly driven by three main basins: Santos, Campos and Espirito Santo. In 2017, natural gas production reached 22 Bcm per year, compared to 8 Bcm in 2000. The pre-salt fields located in the Santos basin accounted for about 8 Bcm (or 35%) of Brazil’s marketed gas production in 2017, with the majority of the production coming from the Mexilhao, Iracema, Lula and Sapinhoa fields. Most of the gas produced from the pre-salt fields is associated gas, and this will be the main driver of supply growth in Brazil 2030. The Buzios, Iara and Libra fields are forecasted to add almost 14 Bcm to Brazil’s natural gas production by 2030, driving total production to around 47 Bcm per year.

Due to the lack of offtake infrastructure from the offshore fields to mainland, significant volumes are currently re-injected or flared. These volumes amounted to about 10 Bcm in 2017, roughly the same as the total pipeline imports from Bolivia. Last year, however, Petrobras was able to reduce re-injected volumes by 1 Bcm year-on-year as a second pipeline, Route 2, began operating increasing offtake capacity from the Santos basin by 4.7 Bcm per year. This comes as an addition to the Route 1 pipeline bringing total capacity to 8.4 Bcm per year. A third pipeline, with another 6.6 Bcm per year capacity, is under construction and is expected to start up in 2020, routing pre-salt gas to the state of Rio de Janeiro where there is high demand for gas. In addition, there are plans to build a fourth pipeline with a capacity of 5.5 Bcm per year connecting the Santos Basin to Cubatão in São Paulo. With these additions, the total pipeline capacity could increase by 16.8 Bcm per year and would help eliminate the bottleneck that currently constrains production at the Santos Basin.

Consumption

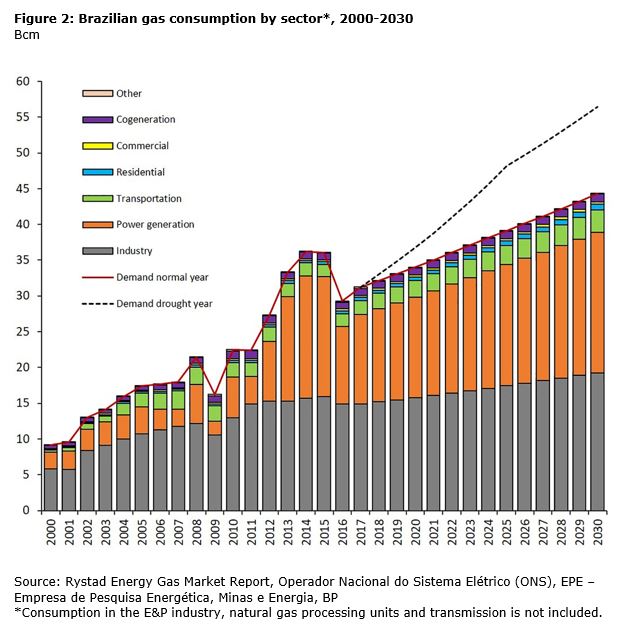

Natural gas consumption in Brazil has grown steadily since 1999 when the Bolivia-Brazil pipeline (GASBOL) was commissioned. Brazil consumed 31 Bcm of natural gas in 2017, which is triple 2000’s consumption of 9 Bcm. The industrial and power sectors account for roughly 90% of gas demand in Brazil with the remainder taken up by transportation, residential and others. Although the industrial sector has been the largest gas consumer historically, the share of industries in the gas consumption mix has dropped to around 50% due to a prolonged drought, which caused increased demand in the power sector.

Gas consumption in the power sector in Brazil is volatile and highly dependent on the availability of hydropower. In 2011, a comparatively wet year, the power sector consumed 3.8 Bcm of gas, which was a 34% drop from 2010. One year after, Brazil entered its worst drought in more than 80 years. Gas-fired plants used 8.4 Bcm to produce power, a 120% increase from 2011. The impact of unpredictable precipitation patterns makes gas demand in the power sector follow no predictable pattern and leaves gas E&P companies with additional uncertainty. This also makes it very difficult for independent power producers to secure long-term gas supplies to win power auctions.

Historically, 80% of Brazilian power has been produced from hydro plants and 5% from gas plants during normal years. When abundant water supplies were not available in a period of rising temperatures and diminishing precipitation during 2012 and 2015, the hydroelectric share in the power generation mix fell to 60% and gas jumped to 14%. Although power plants burning natural gas were operated at capacity during dry years, millions of people were still hit with power outages. Brazil needs greater diversity in their power generation mix in order to form a stable base load. The Brazilian government has therefore announced its intention to restrict the construction of hydroelectric plants with large reservoirs favoring instead run-of-river hydro capacity and wind power. Rystad Energy forecasts installed capacity from wind power in Brazil to grow to 30 GW in 2030, a 150% increase from the 2017 level. The gas-fired power capacity is expected to grow to 25 GW in 2030, a modest 20% increase from 2017.

Assuming economic growth remains stable, Rystad Energy expects Brazilian gas demand to increase to 39 Bcm by 2025 and 44 Bcm by 2030. Industrial demand will grow at a low rate of 2% per year and achieve 19 Bcm by 2030. Gas use in road transport is forecasted to increase by 3% per year to 3 Bcm in 2030, given Rystad Energy’s house view of oil prices trending up towards 2030. In that there is no space heating need in Brazil, we think gas demand in residential and commercial sectors will more or less stay the current level. The outlook for gas demand in the power sector remains uncertain. As hydro power highly depends on precipitation which is hard to forecast and as we see additional renewables capacity is preferred over gas, gas for power is expected to arrive at just 19 Bcm by 2030 in normal years and 31 Bcm in drought years.

Balances

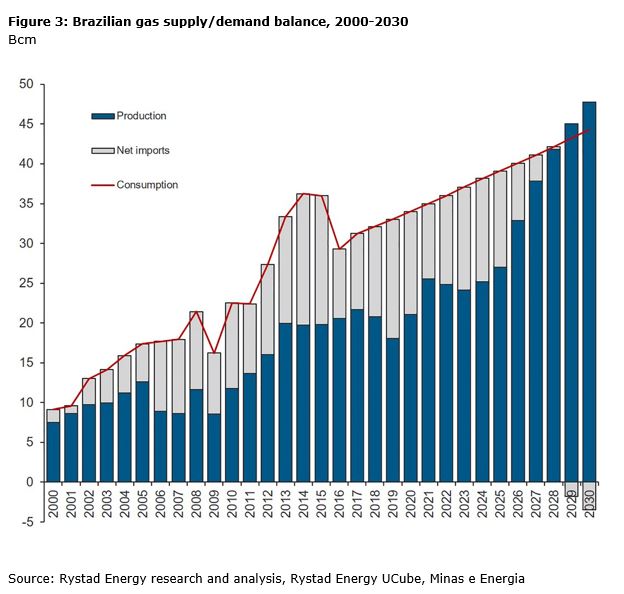

Based on the forecasted demand during normal years, we see consumption outpacing production despite the large potential from major gas fields. As a result, Brazil is expected to be a net importer until the end of the next decade. Historically, Brazil has had net imports every year since the startup of the GASBOL-pipeline from Bolivia in 1999. The gap between domestic gas demand and domestic production increased through the start of this century and was especially evident during the production drop around 2006 and the drought years of the early 2010s as can be seen in Figure 3 below. We even saw net imports to Brazil throughout the recent economic downturn despite the drop in gas demand. The future net imports entail a continued dependence upon the main supply sources, Bolivia and LNG.

Bolivia is the main supplier of gas to Brazil. The GASBOL-pipeline has a capacity of 11 Bcm per year, which also reflects the yearly contracted gas volumes between the two countries. The 11 Bcm take-or-pay gas contract is held by the two major state-oil companies on either side, Petrobras and YPFB, and has covered Bolivian export volumes through GASBOL since it started up. Although we saw lower delivered volumes in the beginning, the flows from Bolivia to Brazil have increased steadily and have remained around capacity over the last 10 years.

LNG imports, on the other hand, were not possible until the first regasification terminals started up in 2009. Now Brazil has three LNG import terminals: the Pecém, the Guanabara and the Bahia. The total capacity of these terminals is close to 16 Bcm, but they are dependent upon FSRUs to receive the cargoes. LNG import volumes have varied since 2009 as they have only imported LNG when needed. The highest annual import volume of approximately 7.3 Bcm was imported during 2014 due to the large need for gas in the power sector.

Argentina has also played a minor role as a gas exporter to Brazil, however, the volumes have been small and they are not forecasted to have sufficient domestic production to cover even their own consumption. Let alone export to Brazil.

During the next ten years, we see both Bolivia and the global LNG market continuing to supply Brazil with gas. However, stable, Bolivian exports are expected to fall and make way for a larger share of LNG volumes. As the Bolivian contract expires next year and there has been talk of reducing the dependence on Bolivian gas, we expect to see lower contracted gas volumes from Bolivia going forward. Unless Bolivia is able to turn around its declining gas production with the recently announced Los Monos gas field, exports to Brazil are expected to drop after 2020 as supplies from the Andean country wane.

This leaves LNG imports to cover the remaining gap. Since we do not see future net import volumes above 15 Bcm, the current regasification capacity should be sufficient to cover future volumes. However, new planned terminals have already been announced, such as the terminal in Segripe. The global supply of LNG has expanded rapidly during the 2010s, predominantly led by Australia and the US, which has resulted in a looser market. However, Asian appetite for gas during the previous winters has revealed that the market is not as oversupplied as what many believed. And despite seeing proposed global liquefaction projects with a combined capacity of more than 1000 Bcm, the slow sanctioning activity could cause a tight market already in the beginning of the 2020s. As a result, Brazilian LNG prices would have to converge towards Asian LNG prices to attract cargoes.

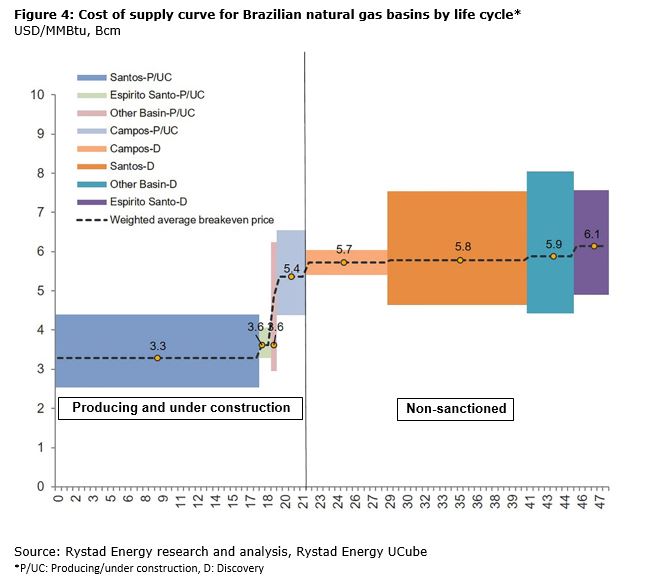

Rystad Energy expects the Asian Spot LNG price to average approximately US$7.8 per million Btu in 2018, before falling in 2019 and 2020 due to excess supply in the market, which will affect spot prices. However, from the early 2020s the tight market will lead prices to increase to nearly US$9.8 per million Btu in 2025. In comparison, the costs of domestic gas will be significantly cheaper than the price of imported LNG. Currently producing fields in Brazil have an average breakeven price in the range of $3.3-5.4 per MMBtu (see Figure 4). Pre-salt fields in the Santos basin are Brazil’s biggest and cheapest source of natural gas with an average breakeven price of $3.3 per MMBtu, emphasizing the economic opportunity for Brazil of making these volumes available for the domestic market.

Nevertheless, despite the economic advantage of domestic supplies, the gas volumes brought to the market during the next ten years will not cover the forecasted gas hunger and Brazil will look outward for additional supplies. However, the change in the pace of production from 2025 will lead domestic production to catch up with demand and result in declining imports. Thus, Brazil has the potential to enter the following decade as a net exporter of natural gas.

(By Carlos Torres Diaz, VP Gas & Renewables Markets; Xi Nan, Senior Analyst; Sindre Knutsson, Senior Analyst, and Iben Fürst Frimann-Dahl, Analyst, all Rystad Energy. Original article published in the July 2018 edition of LNG Industry magazine, click here to see the original article.)

***